[ad_1]

The week began with a government plan coming to light, of using senior bureaucrats to “showcase” and “celebrate” its “achievements” and to reach out to past and future “beneficiaries” of the Centre’s welfare schemes. It ended with the Election Commission stepping in to direct the government that the programme is not carried out in the five election-bound states.

If things had gone according to the government’s plan, officers designated as “rath prabharis” would have participated in the nation-wide “Viksit Bharat Sankalp Yatra”, to be flagged off by the Prime Minister in November. Now, not only will the yatra skirt poll-bound states, where the Model Code of Conduct has come into force, but the government has also decided to call them “nodal officers”, not “rath prabharis”.

This episode may have come to a satisfying end — an overstepping government stands rebuked by a vigilant monitorial institution. But look again, and this is not the end of the story. There are things it has to say — not about transgressive politics and its comeuppance, but about what is seen to be politics-as-usual.

The fact is that governments routinely draft bureaucrats into party-political programmes. And this is related to the reconstitution of governance and the architecture of welfare schemes. On both counts, the BJP is a prime change-maker, if not the sole driving force behind the changes.

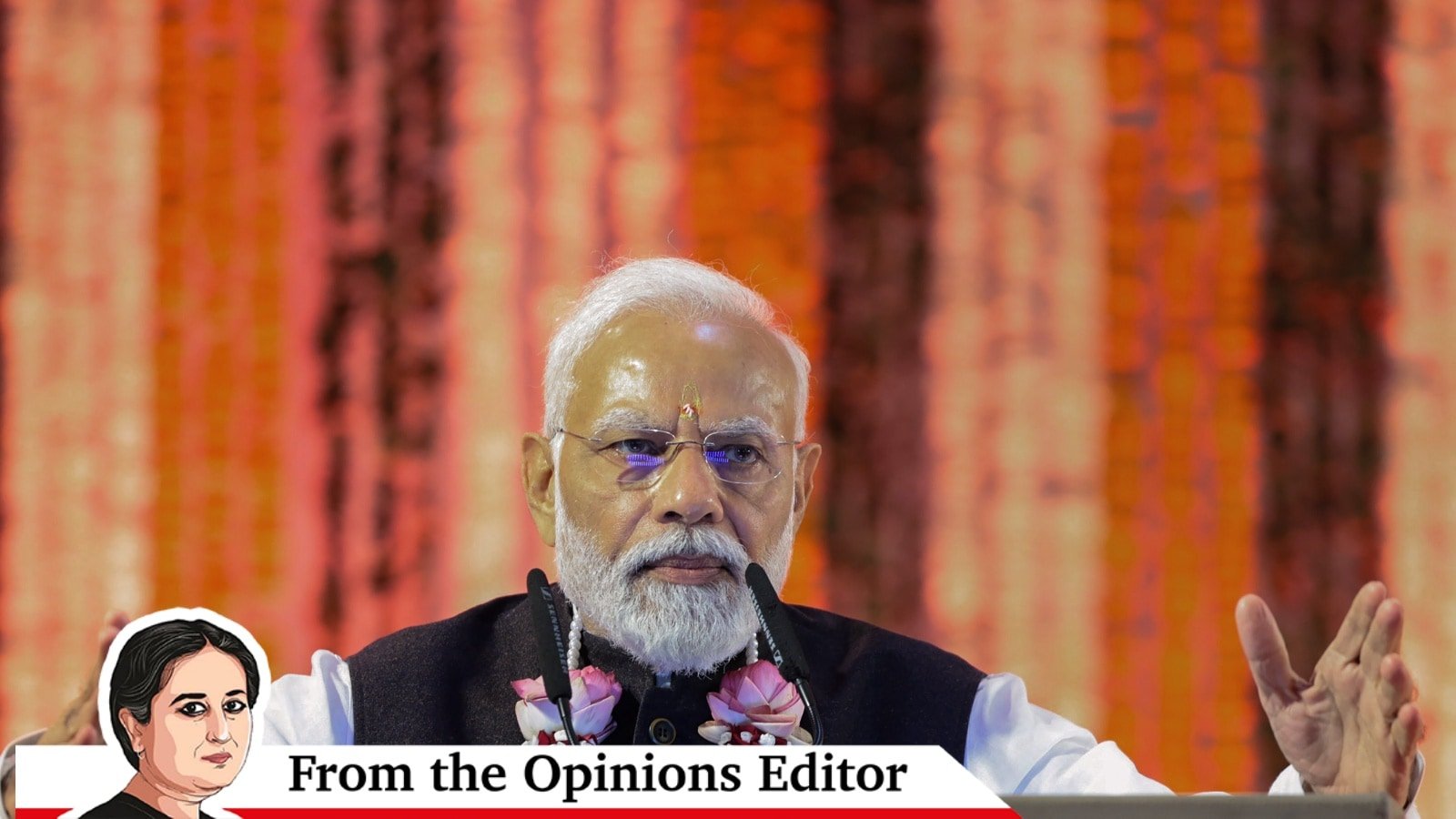

The political primacy to bureaucrats is not just a function of the growing complexities of governance in a large and aspirational country. It flows from a model adopted by the Narendra Modi-led BJP at the Centre and by chief ministers in several states, in which the PM/CM prefers to govern directly through a favoured set of bureaucrats. This is in order to centralise power, claim full ownership and take the whole credit, by cutting out intermediaries — other central ministers or state governments, for instance, in the case of central schemes.

At the Centre, PM Modi is projected as the Only One Who Makes Everything Possible — “Modi hai to mumkin hai”, goes the slogan. In the state, CM Nitish Kumar, throughout his long years in power in Bihar, has invited accusations of promoting “afsar shahi” or rule by bureaucrats. This is a form of personalised governance that has place in it only for the faceless implementers of the Leader’s policies, not for ministers or leaders or troublesome allies, for that matter, who may demand their share of power and negotiation, acknowledgement and credit.

Of course, efficiency- or corruption-based arguments can be made in favour of such a centralised model of governance — by cutting out his ministers and partymen, the argument goes, the Nitish government has cut down the political delay and rent-seeking that were a larger part of government projects before him. Even if that were true, there are clear and long term costs to this governance model — in the form of a politicised bureaucracy that wears its loyalty to the government of the day on its sleeve. That cannot be good news for a system that counts on its steel frame to impart stability and continuity, as governments come and go.

Related to this phenomenon of the Leader centralising power and acting through his chosen officers who do his bidding, is another one — the political recasting of the delivery of welfare by the state to citizens, who are now seen as beneficiaries or “labharthi”.

Delivery of goods and services by the state has been transformed by non-political factors and forces too — by the rapid strides of technology, for one, which makes possible direct benefit transfers in cash and kind to individual households. But it is being changed, more potently, by the Modi-BJP’s re-imagination of welfare, or the New Welfarism.

Most Read

As former chief economic adviser Arvind Subramanian has described it, the Modi government’s New Welfarism does not prioritise the supply of public goods such as basic health and primary education and it is less than enthusiastic about shoring up the existing safety nets. It has directed its energies, instead, to the subsidised public provision of essential goods and services, normally provided by the private sector, such as cooking gas, bank accounts, electricity, housing, toilets and water, apart from a surge in cash transfers. These are “attributable tangibles” that carry the Leader’s personal imprimatur, they benefit people today rather than at an indeterminate point in the future.

Just as the notion of a neutral bureaucracy is a casualty of the personalised governance model that drafts in the civil servant, the public provision of private goods to individuals relegates the more abstract notion of the rights-bearing citizen who has a claim to state welfare. It redefines empowerment as access to specific benefits, addresses the citizen as beneficiary or “labharthi”.

The EC may have stopped the Viksit Bharat Sankalp Yatra from making stops in the five poll-bound states, officers-cum-rath prabharis in tow. But the larger juggernaut of welfare politics, as transformed by the BJP, rolls on.

Till next week,

Vandita

Must Read Opinions from the week:

– Editorial, “Officer and prabhari”, October 25

– Editorial, “Mumbai alarm bells”, October 26

– Fali Nariman, “SC does not have the authority”, October 27

– Saurabh Kirpal, “Court lets itself, and us, down”, October 27

[ad_2]