[ad_1]

In 1901, when Edward VII succeeded as the British monarch after the death of Queen Victoria, Lord Curzon as the Viceroy of India organised a formal proclamation for the accession to the title before the princes and people of India. An Imperial Assemblage had previously been held in Delhi in 1877 as a visual announcement of the British domination over India and the investiture of the title of Kaiser-e-Hind on Queen Victoria, but this time the grandeur was far greater. The 1903 event had all the trappings of oriental splendour, including a procession of 48 princes from across India riding on elephants. The procession was led by Curzon and his wife, Mary, on the first elephant, followed by the Duke and Duchess of Connaught on the second elephant.

On view at DAG gallery in Delhi, a 1903 chromolithograph on paper documents this magnificent scene of the procession. The depiction forms part of the exhibition “Delhi Durbar: Empire, Display and the Possession of History”, which closes on November 6. Curated by historians Swapna Liddle and Rana Safvi, the photographs and antiquities from the DAG collection demonstrate “the trajectory of Delhi within the British imperial imagination”. Through the three grand durbars — 1877, 1903 and 1911 — the narrative also records the period and politics of the time. “There is an effort made to present the modern Indian perspective… A lot has been written about the durbar, but mainly from the imperial lens. The durbars were primarily held to legitimise and popularise colonial rule. There was an evident appropriation of Mughal symbols, from the use of the word durbar to the architecture of the domes, jharoka darshan, the elephant parades,” says Safvi.

The Imperial Durbar of 1903 (Credit: Delhi Art Gallery)

The Imperial Durbar of 1903 (Credit: Delhi Art Gallery)

So, before the grandeur of the durbars, visitors are given a ‘darshan’ of the great monuments of Delhi, and the revolt of 1857 that marked the end of the rule of the East India Company, and the direct rule of the British Crown in India. Covering one wall is a map of Imperial Delhi from the 20th century that shares the layout of the Capital that was to be built at Raisina. “The British acknowledged the importance of Delhi in the minds of people, even during the decline of the Mughals. There was an aura of power that surrounded the city and people across the country saw it as the Capital… The holding of the durbars in Delhi is also to tell them we are your familiar empire, with the same Capital that you acknowledge. The 1911 transfer of the Capital becomes a culmination to that narrative,” says Liddle.

The exclusion of the average Indian is evident — both behind the camera and also in the audience at the durbars. While the 1903 durbar had an amphitheatre in the shape of a horseshoe to accommodate 16,000 invitees, three times the number seated in 1877, it was only in 1911 that provisions were made for the general public. Held in the presence of the monarchs, King George V and Queen Mary, it is here that the announcement was made for transfer of the capital of British India to Delhi. The exhibition has a pair of 60×40-inch oil on canvas of the two monarchs painted by H Banerjee, and photographs that share the arrangements and the ceremonies — from the throne pavilion designed in Indo-Saracenic style by architect-engineer Swinton Jacob, to the extravagant princely camps that were set up. Arranged in a glass vitrine are William Britain’s enameled collectible figures from 1903, that include bangle sellers with baskets, shepherd with goats and a snake charmer. “There were military reviews and ceremonies in the mornings, polo matches, balls, dinners and state receptions in the evening. Visitors were transported by the ship SS Arabia from England and by train from Bombay,” writes Safvi, in a book accompanying the exhibition.

Most Read

Over the years, as the colonial perception evolved, the durbars, too, reflected the ground changes. “In 1877, the focus was on the princes of India, which continued to a large extent till 1903. It is believed that the people of India will follow the traditional princes, and there is contempt for the national movement and the educated class asking for democratic rights. By the time the last durbar was held in 1911, there was growing liberalism in Britain, and the British acknowledged the need to take into account the Indian demands for greater participation. So during the state entry procession, there were stands for school children, and a special tent for the representatives of British India. The fact that the king addressed them, signifies that they were considered important,” says Liddle.

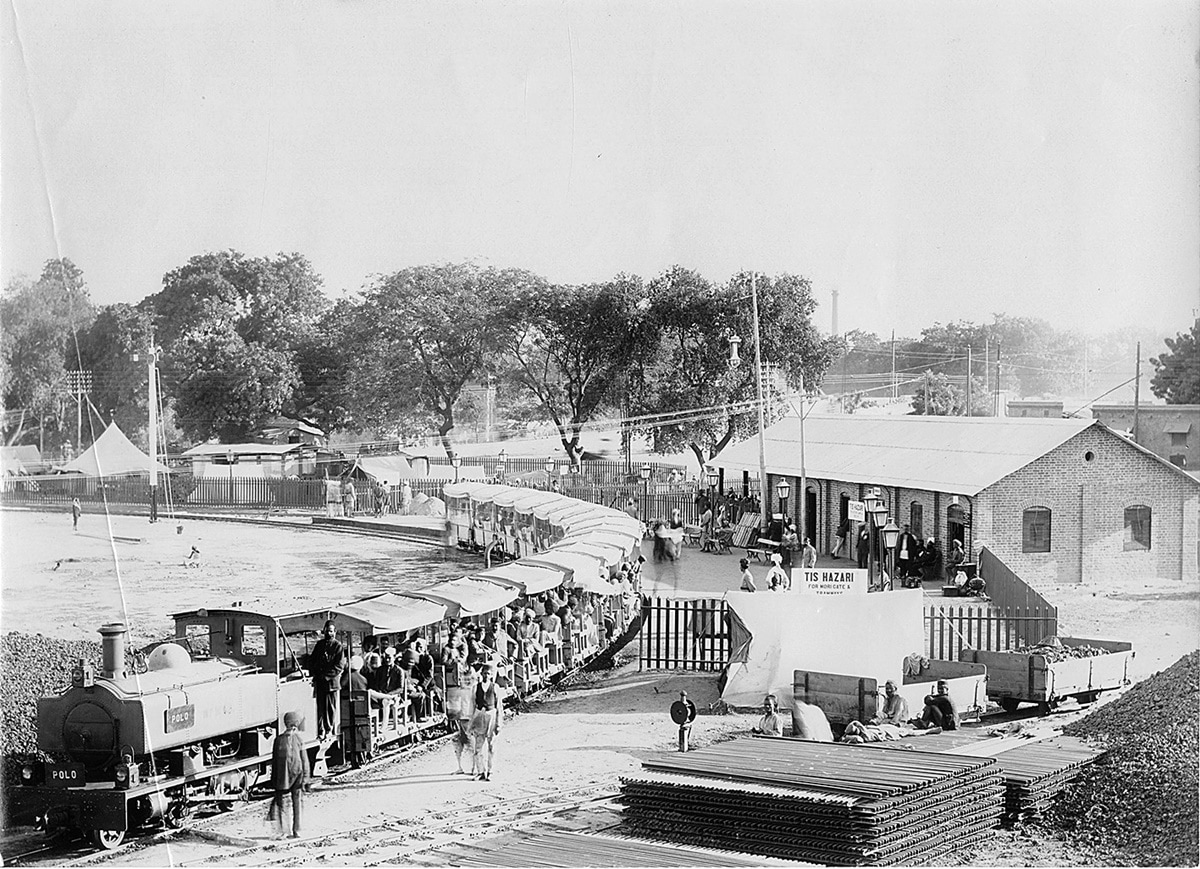

The 1911 Durbar Railway (narrow gauge at Tis Hazari Station) (Credit: Delhi Art Gallery)

The 1911 Durbar Railway (narrow gauge at Tis Hazari Station) (Credit: Delhi Art Gallery)

Though works from the period fascinate and enrich, a reading of them through the accompanying text and details in the book give a complete picture. For instance, we are told that according to some accounts once it was only the King of Delhi who was allowed to pass through the Delhi Gate of Red Fort when he went to the Jumma Masjid to worship. A 1903 photograph of the state entry procession during the durbar also reveals the introduction of electricity in Delhi, with electric wires and poles visible in a scene from Chandni Chowk. Alongside postal stamps from the Coronation Durbar of 1903 on display, we are informed of an elaborate postal system with 27 post offices set up for the durbar. “Among the clerks employed in it were men who could read almost every known vernacular used in the Indian Empire, from Kashmiri to Burmese, to say nothing of Persian and various foreign languages,” reads a quote by Stephen Wheeler attributed to his book History of the Delhi Coronation Durbar.

Liddle says, “While it was important to introduce certain things as a matter of convenience at the durbar sites, these also became an occasion for the British to showcase the progress that India had made under their rule. It becomes part of that propaganda. The official narrative presents it as the building of a new modern city in the wilderness of India.”

[ad_2]

Source link